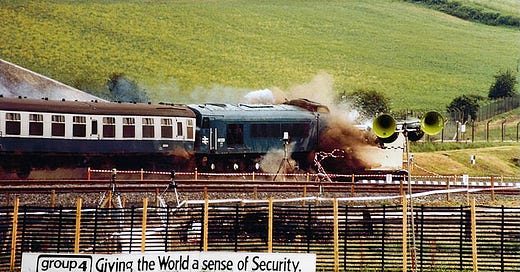

In 1984, about 100 miles north of London, a three-coach train travelling at 100 MPH smashed into a derailed cargo carriage holding a steel flask prominently labelled “RADIOACTIVE”. The multiple layers of protective shielding and shock absorbers worked perfectly; the container sustained only a minor dent and none of its contents were spilt.

As you can imagine, the event made the evening news – but not because anyone was concerned about injuries, or that nuclear material had nearly been scattered over the English countryside. In fact, the whole thing was a carefully scripted test, with the train being run by remote control, steel bars replacing the irradiated fuel rods that would normally be held within the vessel, and an audience enjoying packed lunches in specially-constructed bleachers nearby. The manufacturers had already dropped and burnt similar flasks and crashed model trains into each other, but that wasn’t enough–the rail operator and the public demanded a full-size experiment with genuine rolling stock on an actual track to demonstrate that the safety systems really worked. And to add a typically British touch of whimsy, the whole spectacle was organised by Terry Pratchett, before he started writing funny books about planets carried on the backs of turtles.

I was reminded of Sir Terry’s simulated catastrophe when, in the wake of hospitals and emergency services wiped out by the recent blue-screen computer epidemic, health-care expert Professor Joe MacDonald told me that medical operators “generally rely on the likes of Microsoft and CrowdStrike to test things properly before they are released into the wild.” He and I agreed that this is lunacy–like British Rail in the 1980s, we should follow the Russian proverb and “trust, but verify” on our own kit when it comes to critical infrastructure. Sadly, UK health regulations seem to prescribe no checking in situ at all, so we don’t have “red teams” sending digital locomotives racing toward derailed operating systems, just misplaced belief in providers like CrowdStrike–who admitted last week that they forced customers to accept instant updates to their live systems and didn’t even permit local testing. In tightly coupled systems like transport, finance, and healthcare, where a small failure rapidly propagates with disastrous consequences, uncheckable software should be kicked to the curb–and even if your systems aren’t life-critical, you should be looking at alternatives too.

The good news is that there are standard practices your tech team can start using today to prevent future Blue Fridays from turning your computers into expensive bricks. The simplest one was first discovered by miners: just as canaries detected carbon monoxide in the pits before the colliers could smell it, you can make changes in a group of test machines first, letting any problems emerge there, and only when these “canaries” are all clear, gradually deploy those changes to a small group of customers, then a few more, and so on. (Yes, CrowdStrike should have done this kind of slow rollout themselves rather than delivering a buggy update to 8.5 million computers simultaneously–but the lesson of 19th July is precisely that you can’t outsource disaster prevention to your suppliers.) And you can borrow another trick from occupational-health advocates, who have been using “safe by design” principles for several decades now: coders and architects can choose from a wide variety of tools that detect and prevent imminent footguns. For example, antivirus programs like Falcon Sensor, the one at the centre of the blue-screen disaster, can be shielded by a type of “supervisor code” called eBPF that checks for problem behaviour before the software even runs. In any case, we need to stop castigating others (CrowdStrike, Microsoft, regulators–a Belgian newspaper even blamed the USA for the outage, bizarrely) but instead begin looking inward, reviewing our own software supply chains to find and root out any path to production changes that isn't double-checked.

This first appeared in my weekly Insanely Profitable Tech Newsletter which is received as part of the Squirrel Squadron every Monday, and was originally posted on 29th July 2024. To get my provocative thoughts and tips direct to your inbox first, sign up here: https://squirrelsquadron.com/